By Amanda Tapp

Introduction

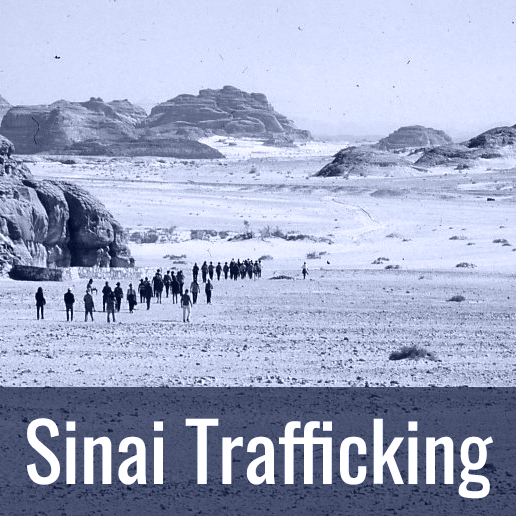

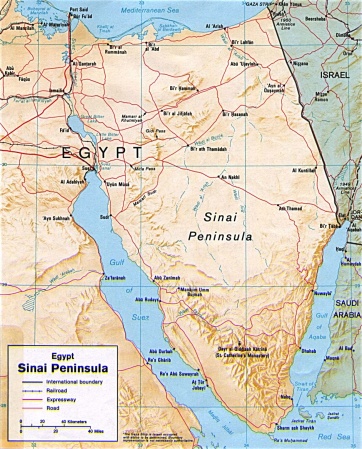

The Sinai desert of Egypt, bordering Israel, connects the Middle Eastern world to the continent of Africa. Its strategic position acts as a corridor for human trafficking in the MENA region and a critical area for the ransom of humans, most of whom are Eritreans. This phenomenon, called “Sinai Trafficking”, began in 2009 and continues up to this day.

It is impossible to estimate an accurate number of victims, due to nuance in the definition of “victims” and the very covert nature of the issue. However, the European Parliament presented a report stating between 25,000 – 30,000 people between 2009 to 2013 were victims of Sinai Trafficking (Kestler-D’Amours 2014). Approximately 25% of hostages held in the desert die- a number considered “conservative” at best (Reisen, Estefanos, Rijken 2013, 66). Through this article, I will look at the roots of the phenomenon, and offer bespoke solutions to the Sinai Trafficking.

The Victims and the Aggressors

Ninety-five percent of the hostages that fall victim to Sinai Trafficking are Eritreans (Berhe 2014). These Eritreans asylum seekers, exploited by the trafficking network in the Sinai. This network in the Sinai is comprised of multiple different parties, including high-ranking Eritrean and Sudanese officials (many coming from the Rashaida and Hidarib tribes), as well as Bedouin circles. The Eritrean and Sudanese officials include the Eritrean Border Surveillance unit, which has been found to be privy to taking bribes, controlling the prisons in Eritrea and the military camps, and General Teklai Kifle (“Manjus”)- the principle Sudanese official leader of smuggling Eritreans on the Sudanese side of the border (United Nations 2012, 21). The Bedouin circles in the Sinai and Sudan play a part by keeping the hostages in their homes, often demanding a ransom from the victims’ relatives.

Eritreans often pay smugglers to get them past the Eritrean border, and are then picked up by “guides” who then sell them to Bedouins, or are exploited and sold within refugee camps like Mai Aini in Ethiopia, or Shagarab in Sudan. Many of these Eritrean refugees are held ransom by Bedouin families and subjected to torture while calling their families to let them know and to collect ransom money. Torture methods include beating, electrocution, burning, mutilation, amputation, rape and sexual violence (Reisen, Estefanos & Rijken 2012, 72). The health of these victims is not of consideration, as they are merely commodities – as long as they are alive, they will be profitable to the human traffickers. The primary purpose of the aggressors is to put pressure on the families of victims in order to extort the high ransoms demanded.

Push and Pull Factors

Push and pull factors are useful in understanding the dynamics of a particular human trafficking phenomenon. Push factors refer to the factors driving people from their countries, while pull factors refer to the factors that draw people to another location. In this case, push factors from Eritrea are ample, as since 2001 President Isaias Afwerki has ruled Eritrea as a one-party state with no elections. An estimated 5,000 Eritreans flee this totalitarian country every month (Berhe 2014). Main factors contributing to this include the Eritrean-Ethiopian War (1998-2000), which has led to masses of refugees ever since, and political repression and corruption. The lack of rule of law and civil liberties, unpredictability in the system, the use of extortion to control the Eritrean diaspora, and widespread poverty and unemployment, are all push factors.

According to online database Trading Economics, Eritrea is one of the poorest countries in the world, with their GDP value representing 0.01% of the world economy, averaging 1.27 billion US dollars between 1990 – 2014. The mandatory “National Service” is one of the biggest push factors. The “National Service” has no end-date, and includes many type of labour – forced labour, child labour, with civilians earning just 800 nakfa (~£40) a month from national service (Smith 2015). Eritreans between the ages of around 18 and 50 are required to join, which causes many youth and minors to flee. Furthermore, difficulty in obtaining an exit visa and the shoot-to-kill policy at the Eritrean-Ethiopian border add starkness and desperation to the situation.

The Sinai acts as a pull factor primarily due to its strategic location- acting as a corridor to places that provide better opportunities. The main destination goal for the Eritrean refugees going through the Sinai is Israel, perhaps seen as attractive due to its supposed Western values.

The Sinai Trafficking Cycle

The coining of the “Sinai Trafficking Cycle” accurately represents the difficulty of escaping from the enclosed, circular process these refugees become victim to. When fleeing to refugee camps or elsewhere they face the likelihood of being recruited, abducted, or sent back to Eritrea where they face persecution. As a result, their quest for asylum is often that of a pipe-dream. This shows the problem is not limited to one locality, but rather is dispersed, which therefore requires a multifaceted examination of the phenomena.

The first stage of the Sinai trafficking cycle takes place within Eritrea, where many are forced into labor, often times in the mandatory “national service” for an indefinite period of time (Reisen & Rijken 2015, 121). The second stage of the cycle occurs in Sinai, after fleeing Eritrea, where they are smuggled and trafficked for the purpose of financial gain. Upon escaping the second cycle, many Eritrean refugees then find themselves being exploited by Egyptian authorities in detention centers or on the streets. (Reisen & Rijken 2015, 121). The continuous extortion these victims face, (as, even if the refugees manage to escape Eritrea, they fall victim to extortion in the Sinai, or even in Israel or Egypt) requires that the solutions should not be constrained to the conventional anti-trafficking methods of Prevent, Protect and Prosecute. Instead, the solutions to address this cycle must be nuanced, and similarly address the multiple roots of the problem. The solutions must encapsulate not only the push factors of Eritrea, but also the relevant countries and their involvement in the Sinai Trafficking cycle – namely Egypt and Israel.

Solutions

The UN’s (United Nations) “Global Plan of Action” approach towards human trafficking was launched in 2010. The accumulated research, data collection, and an increased hope to engage multiple actors, resulted in a unified approach to end human trafficking in all its forms, “coordinated and consistent across the globe”, engaging non-governmental organisations of civil society and the private sector as well as governments and criminal justice systems (UN Press 2010). Under this the governments involved would increase action to protect victims, to prosecute traffickers, in what they termed a “human rights centered approach”, as well as encouraging member states of the UN to contribute more to the Trust Fund that works on fighting trafficking (UN Press 2010). This “human rights centered approach” worked on giving those marginalised a voice addressing women’s vulnerabilities, combating poverty, and fighting discrimination (UN Press 2010).

While the UN’s “Global Plan of Action” unifies and solidifies measures to battle human trafficking, it falls short when implementing methods in specific regions, as it fails to take into account the cultural contexts of each situation, such as the mountainous terrain of the Sinai Desert and its surrounding region. It overlooks the “cycle” aspect of the Sinai Trafficking cycle, which is fundamentally detrimental, from the beginning, in constructing feasible solutions.

Regarding the human trafficking in Sinai, these are the following solutions that may be taken into consideration when combating human trafficking in the Sinai Desert, taken from Reisen, Estefanos & Rijken’s 2015 The Human Trafficking Cycle: Sinai and Beyond.

Governmental Solutions

The first part of the solutions offered to combat the Sinai trafficking in this article addresses governments.

Egypt.

As the Sinai is part of Egypt and therefore acts as the gateway and corridor for these Eritrean refugees to reach Israel and other places with better job prospects, the Egyptian government has a lot of potential influence but still falls short regarding the Sinai Trafficking phenomenon. The Egyptian government has been condemned by Amnesty International for its corruption in the ways they are cracking down on human trafficking in in the Sinai (Amnesty International 2017-18). Furthermore, it may be noted that the Egyptian army is currently engaging in military operations that are focusing on North Sinai, with a focus on combating drugs and terrorism, and therefore less attention has been given to the Sinai Trafficking phenomenon.

The Egyptian government must ensure more resources are available for observing and handling the main sites subject to Eritrean trafficking in the Sinai. This may be done by increased communication with the Bedouin leaders, keeping in accordance with Egypt’s Law 64 regarding Combating Human Trafficking and prohibiting deportations that are in violation of the non-refoulement principle- the prohibition of forcing refugees or asylum seekers to return to their respective countries due to fear of persecution (UNHCR 1977). Many survivors of Sinai Trafficking are “put in prison in Egypt in detention centres, without charge and access to legal process”, thus requiring stricter oversight of these facilities by governments or by external organisations (Reisen & Rijken 2015, 122).

Israel.

The Egypt-Israel route is also now “a notorious spot of human trafficking”, particularly of Eritreans (Mekonnen & Estefanos 2012, 13). As a result, Israel is the primary destination for many of the Eritrean victims in the Sinai Trafficking phenomenon. One of the ways in which Israel may combat the Sinai Trafficking phenomena is by focusing on its current regulations that may permit the “Trafficking Cycle”.

The Anti-Infiltration Law from 2012 was originally instilled in 1954 under the Prevention to Infiltration Law, defining its “infiltrators” as Palestinian or nationals from other Arab countries Israel was not allies with (Human Rights Watch 2012). Israel, since its instalment as a state on May 14th, 1948, has been in five wars with its Arab neighbors- partially shaped by a very strong emphasis on insularity, and which has, in turn, strengthened this defensive, insular rhetoric. Today the Anti-Infiltration Law has been amended to include and also focus on Eritrean migrants. Israel’s fence built along the Israeli-Egyptian border acts as one of the methods to keep the Sinai refugees and fleeing hostages out, deeming them “infiltrators”. The increasingly steady influx of Eritrean refugees attempting to enter Israel has resulted in the Israeli government “actively blocking their entry” and “criminalizing Sinai survivors” (Reisen et al. 2013, 101). Because of these factors, Israel should re-think this anti-African migrant policy. Furthermore, due to Israel’s prominent impact in the Sinai “Trafficking Cycle”, there should be more NGOs within Israel that dedicate more resources to the reintegration of Sinai survivors.

Eritrea and Sudan.

The Eritrean government is arguably the biggest proponent in causing a mass exodus of Eritrean refugees initially. However, in terms of anti-trafficking measures, they become irrelevant to combating the Sinai “Trafficking Cycle”. Instead, pressure from the international community on the Eritrean government to seek international cooperation and to abide to international human rights standards, through incentives or pressure, would decrease the push factors that first enabled this phenomenon. Similarly, the Sudanese Government should also be pushed to seek international cooperation and to abide to international human rights standards. The Sudanese government may allocate more resources to their refugee camps, ensuring they are not used as hot-spots for human traffickers. Perhaps most importantly, overall cooperation between Egypt, Sudan, Israel, And Eritrea in the fight against the Sinai Trafficking phenomena is necessary.

Institutional Solutions

The second part of solutions offered to combat the Sinai trafficking phenomenon in this article addresses international humanitarian organisations.

Law enforcement.

Police and law enforcement agencies like Interpol and Europol may allocate more resources to the specific phenomenon of the Sinai trafficking trade, examining and following money flows and routes. Increased intelligence gathering on the practice of human trafficking occurring in the Sinai is necessary. As one of the main aggravating factors of the Sinai trafficking phenomenon is the strong involvement of corrupted high-ranking officials, namely Eritrean, Sudanese and Egyptian military and security personnel, their communication should be facilitated. Increased cooperation through more intelligence sharing between the agencies and security forces of these countries is necessary.

International organisations.

The United Nations has already been attentive to the cause and may play a further role in combatting the Sinai Trafficking. The United Nations Security Council may adopt and renew UN sanctions towards Eritrea, going further than its arms embargo imposed in 2017, instilled in response to Eritrea’s supposed ties with Al Shabaab. The United Nations Higher Committee of Refugees may do more for the protection of refugees through higher security, monitoring, and cracking down on corruption within Sinai police and army bases. Member States of the UN: observe the situation in Eritrea, and, upon careful examination, engage in a discussion as to when the time for humanitarian intervention is necessary and acceptable.

UNHCR may also establish reception units at the borders of Eritrea, and strengthen measures to combat corruption within institutions of the authorities, like check-points in the Sinai (Reisen et al. 2012, 68). The European Union may play its part by ensuring the protection of refugees as well as victims of trafficking, proposing legislative measures for the acceptance of Eritrean refugees to other countries, increasing availability and possibility of attaining short-term residence permits to Sinai survivors.

Conclusion

The Sinai Trafficking phenomena may best be understood through its alternative name, “the Sinai Trafficking Cycle.” The Eritreans fleeing their oppressive, poverty-stricken country, only to fall victim to Bedouins tribes and corrupt Sudanese and Eritrean officials in the Sinai, then to face the harsh anti-refugee rhetoric within Israel and Egypt, and corruption of detention camps in Egypt, shows the continuous cycle of extortion. Therefore, the multifaceted and multidimensional aspect of this phenomena must be understood and answered with multifaceted solutions. The governments of the involved countries, namely Israel, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt and Israel, as well as the rest of the governments in the world who hold a certain responsibility to aiding others in need, require more international cooperation and suppression and containment of the corruption that occurs within this trafficking cycle. International organisations and law enforcement may focus on the protection of these refugees in each stage of the cycle as well as shedding light on the significant involvement of high-ranking officials. The Sinai Trafficking cycle sheds light on larger issues within human trafficking, such as the push factors of oppressive regimes like Eritrea and the consequences of a large exodus of peoples fleeing their home.

“The Return Flight” by Selam Kidane

Eritrea

Hide little brother hide

They have come to get you again

Please hold your breath… don’t make any noise

Kassala

Run little brother run

They want to sell you and sell you kidneys

Please don’t stop to breath run don’t halt your pace

Lampedusa

Swim little brother swim

They refuse to come rescue you

Take a deep breath and swim there is no time to think

Eritrea

Fly little brother fly

To the clouds above the sea

To the mountains beyond the borders

To the streets you knew like the back of your hand

Then finally to the home whose very life and light you were

Fly to the side of your forlorn mother who lived for you and will die with you

Rest

Dear brother

Now rest in peace

There is no need to run

And there is nowhere to hide

It really is the end it is all over now

Rest little brother rest in eternal Peace

References

Title Image is By ארכיון גן-שמואל, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7612585

The Return Flight Poem is from : http://www.asmarino.com/writers-corner/1884-the-return-flight

Amnesty International. (2017-18). Amnesty International Report: The State of the World’s

Human Rights. Retrieved from: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/files/2018-02/annualreport2017.pdf

Berhe, Vanessa. (2014). Human Trafficking in the Sinai Desert: A Report On the Origin of

the Crisis, the Current Situation and Possible Future Solutions. Endslaverynow. Retrieved from: http://www.endslavery.va/content/endslavery/en/publications/youth_symposium_2014/sinai.html

Human Rights Watch. (2012). Israel: Amend “Anti-Infiltration Law”: Measure Denies

Asylum Seekers Protections of Refugees Convention. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/06/10/israel-amend-anti-infiltration-law

Kestler-D’Amours, Jillian. (2014). Report: Officials Aid Sudan-Egypt Trafficking. Aljazeera.

Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/02/report-officials-aid-sudan-egypt-trafficking-201421163658367107.html

Mekonnen, Daniel & Estefanos, Meron. (2012). From Sawa to the Sinai Desert: The Eritrean

Tragedy of Human Trafficking. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2055303

Reisen, M.V., Estefanoes, M., & Rijken, C. (2012). Human Trafficking in the

Sinai: Refugees between Life and Death. Europe External Policy Advisors. Retrieved from: http://www.ehrea.org/report_Human_Trafficking_in_the_Sinai_20120927.pdf

Reisen, M.V., Estefanos, Meron., & Rijken, Conny. (2013). The Human Trafficking Cycle:

Sinai and Beyond. Netherlands: Wolf Legal Publisher. Retrieved from: https://www.borderline-europe.de/sites/default/files/background/Small_HumanTrafficking-Sinai2-web-3.pdf

Reisen, Mirjam Van. & Rijken, Conny. (2015). Sinai Trafficking: Origin and Definition of a

New Form of Human Trafficking. Social Inclusion 3(1), 123-124, doi: 10.17645/si.v3i1.180

Smith, David. (2015). Inside Eritrea: Conscription and Poverty Drive Exodus from Secretive

African State. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/23/eritrea-conscription-repression-and-poverty-recipe-for-mass-emigration

Trading Economics. Eritrea GDP. Trading Economics. Retrieved from:

https://tradingeconomics.com/eritrea/gdp

United Nations. (2010). General Assembly Launches Global Plan of Action against

Trafficking in Persons; Secretary-General Says Partnership Only Way to End ‘Slavery in the Modern Age.’ United Nations. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/press/en/2010/ga10974.doc.htm

United Nations. (2012). Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea Pursuant to

Security Council Resolution 2002. United Nations, 21. Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2012/545

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (1977). Note on Non-Refoulement

(Submitted by the High Commissioner). UNHCR. Retrieved from: http://www.unhcr.org/uk/excom/scip/3ae68ccd10/note-non-refoulement-submitted-high-commissioner.html